In July, the Department for Housing, Local Government and Heritage (DHLGH) launched the “Public consultation on Ireland’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive Marine Strategy Part 1: Assessment (Article 8), Determination of Good Environmental Status (Article 9) and Environmental Targets (Article 10),” to which SWAN submitted a response in September.

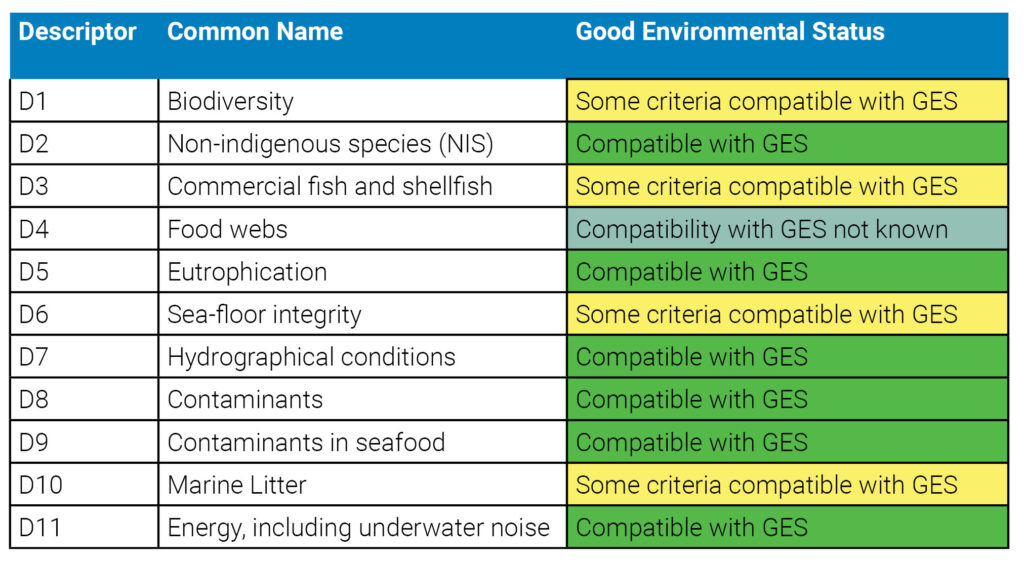

The Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) is European legislation which “aims to achieve Good Environment Status (GES) for all marine waters in Europe and protect the resource base for marine related economic and social activities” (DHLGH). The MSFD was adopted in 2008 and is implemented in six-year cycles. We are currently in cycle 3 (2023-2028), with EU Member States required to report to the EU every two years. It is structured around 11 descriptors, which describe the state of the marine environment, as well as anthropogenic (manmade) pressures on the marine environment. They include topics as overarching as ‘Biodiversity’ (Descriptor 1, which includes pelagic and benthic habitats, as well as bycatch) and as specific as ‘Contaminants in Seafood’ (Descriptor 9). Each descriptor is broken down into more specific criteria of what elements must be met to achieve GES.

11 descriptors of MSFD

In this cycle, Ireland reported six of the 11 descriptors had achieved GES, while another four had partially achieved GES. Descriptor 4, Food Webs, was considered too complex to determine.

SWAN’s Marine Working Group members bring a wide array of expertise on issues as wide-ranging as underwater noise, marine litter and eutrophication. Our MSFD response benefitted from this team effort, bringing in knowledge from our partners such as the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, BirdWatch Ireland, Environmental Forum and StreamScapes. As such, SWAN was able to provide detailed, technical responses to certain descriptors.

In our response, SWAN voiced concern about many of the results. For instance, the findings of Descriptor 3, concerning the pressures and lack of data surrounding commercially exploited fish, are amongst the most alarming in the report. GES was only achieved for 29 stocks of commercially-exploited fish and shellfish and not achieved for a further 46 stocks. Additionally, over half of stocks were not fully assessed and, as in the 2020 report, 99 stocks remain in “Unknown” status. We are dissatisfied that data collection was not improved since the last cycle, nor were improvements seen.

The results seen in Bycatch (the incidental capture of non-target species by various fishing methods), part of Descriptor 1 Biodiversity, are also deeply concerning. Fifty marine species were assessed for incidental bycatch, yet GES was only achieved for 26 (one mammal species, 24 species of fish and cephalopods and one seabird species). We call for urgent measures at both national and EU levels to address the problem of bycatch in Irish waters. SWAN is also concerned at the data deficiency of this assessment, with the bycatch problem not fully understood for dozens of other marine species. Without knowledge of the full extent of bycatch, implementing appropriate measures will be challenging.

Overall, SWAN’s main criticism of this report is the data deficiency that prevented many indicators from being able to be fully assessed for GES. However, we acknowledge that the report is an improvement on previous cycles, with a more comprehensive assessment of Ireland’s marine environment, using a revised set of environmental targets for each of the 11 qualitative descriptors of the Directive and data from 20 monitoring programmes and 36 surveys or campaigns. We call for increased resources both for data collection and monitoring at sea. Utilising reporting from citizen science and environmental NGOs in future assessment and monitoring can increase available data. We reiterate our call from our 2020 response to utilise Coastwatch survey data to assess Descriptor 10 (Marine Litter) and Irish Whale and Dolphin Group’s cetacean records for Descriptor 1 (Biodiversity) and Descriptor 4 (Food Webs).

We also highlighted that in the December 2022 Marine Strategy Framework Directive 2008/56/EC Article 17 update to Ireland’s Marine Strategy Part 3: Programme of Measures (Article 13), there was a measure specifically committing to “By 2023, Ireland will develop stand-alone legislation to deliver the designation and management of an expanded network of marine protected areas [MPAs]; thereby supporting the achievement and maintenance of good environmental status.” As of September 2023, Ireland has still not published MPA legislation. SWAN reiterates the calls of Fair Seas, of which we are a partner, for the urgent publication of the MPA legislation to accelerate the designation of MPAs (including 10% strictly protected) and effective management plans to ensure MPAs are supporting the achievement of GES under the MSFD. The designation of a network of effectively managed MPAs covering 30% of Irish waters is vital to achieving and maintaining GES amongst an array of indicators.

The MSFD is closely linked with other environmental policies such as the Water Framework Directive, Bathing Water Directive, Habitats Directive, Birds Directive and Common Fisheries Policy. SWAN’s remit is to influence water and water-related policy through participation in the implementation of these policies and legislation, so it was important for us to give careful consideration to the latest MSFD report, as we will continue to do for future reports relating to Ireland’s water quality. As an island state with rich biodiversity and unique habitats, it is important we push for an ecosystems-based approach to ensure sustainable connections between marine environment and the people that rely on it.